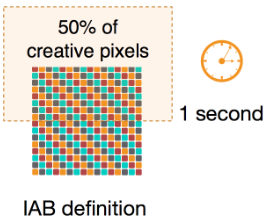

Hello. Let me start by telling you, that viewability is somewhat of a pet peeve of mine. First of all, the word is dumb. It is an artificial creation of the advertising industry, which due to some strange reason does not want to use the perfectly fine “visibility”. Viewability measurement and delivery should be the absolute standard nowadays. According to the definition of the IAB, an advertisement is considered viewable (cringe) when more than 50% of its content was in the viewport for more than one second.

From my point of view, this should be the absolute minimum requirement for an ad to be “delivered”. But interestingly, the guarantee of viewability is not in high demand. We offer the possibility of only paying for viewable impressions, admittedly, for a markup. But simple math leads you to the inadvertent conclusion, that it is well worth investing the markup if you are interested in viewable impressions. Given, that the average viewability rate in the market is 50%, this should be a no-brainer. If we assume a markup of 30%, our viewability product (link) will deliver approximately 150% viewable impressions compared to a traditional campaign for the same amount of money. It continues to puzzle me, why customers still prefer the traditional ‘spend and hope’ over the ‘spend and verify’ approach.

So in this blog post, I want to explain, how we measure and deliver viewability.

Measuring

Viewability itself is measured in the ad unit as part of the JavaScript code. This code detects, if we can measure the viewability and if yes, whether it was viewable. Since we rely on the available APIs, the way of measurement strongly depends on the environment, e.g. mobile web vs. app and which version of APIs and browsers are available.

App

In apps, we first check if a version of MRAID is available. MRAID is a bridge of the native component of an app into the JavaScript container the ad unit is running in. If MRAID is available, we can simply call

mraid.isViewable()

to know, whether the ad is currently visible or not. But since we need not only to know, if the ad unit is viewable, but also for how long, we need to monitor its status. Instead of calling the upper function every couple of milliseconds, we make use of the viewable change event, specified in MRAID:

var mraidEvent = mraid.EventType ? (mraid.EventType.VIEWABLE_CHANGE || 'viewableChange') : 'viewableChange';

mraid.addEventListener(mraidEvent, onMraidViewableChange);

function onMraidViewableChange() {

mraidViewable = mraid.isViewable();

}

If MRAID is not available, we are not able to measure the viewability in apps.

Mobile web

The mobile web comes with a bigger variety of environments. Safari and Chrome are the two main browsers and they come with different capabilites. In addition, the available information depends on the fact, if the ad unit runs in a friendly or unfriendly iframe. An iframe is unfriendly if it is running with a different source than the original website.

1. Intersection Observer

The simplest and most reliable case are browsers which support the IntersectionObserver API. In this case we can simply use the following instructions in order to check whether the ad unit is currently viewable.

var _ioSettings = {

threshold: 0.5

};

var _ioCallback = function(entry) {

isElementVisible = entry[0].intersectionRatio >= 0.5;

};

var elementObserver = new IntersectionObserver(_ioCallback, _ioSettings);

elementObserver.observe(element);

2. Safari painting behavior

In case this API is not available, we try different methods. If the ad is running in a modern Safari browser and in an unfriendly iframe, we can make use of an optimization mechanism of Safari. It prevents the rendering of content in unfriendly iframes if they are currently not in the viewport. Therefore, we are putting a beacon in the middle of the iframe and check whether is rendering. If it is, we know that the ad is viewable.

3. Scrolling

If none of the above methods is applicable, we make use of the browser api to monitor the scrolling of the webpage and calculate the position of the viewport ourselves. This is only possible if the delivered ad unit is either part of the top frame or part of a friendly iframe. However, we try to avoid this method, since it is relatively computing intensive in comparison to the other methods.

By using the presented techniques, we are able to measure viewability in about 80% of all cases.

Delivering

So now we have for each impression the information if a) we could measure the viewability and b) if it was viewable. In general, we count unmeasurable impressions as not viewable. We use this information to deliver campaigns with viewable impressions as primary KPI. Thus, we want to be able to buy viewable impressions for a given price.

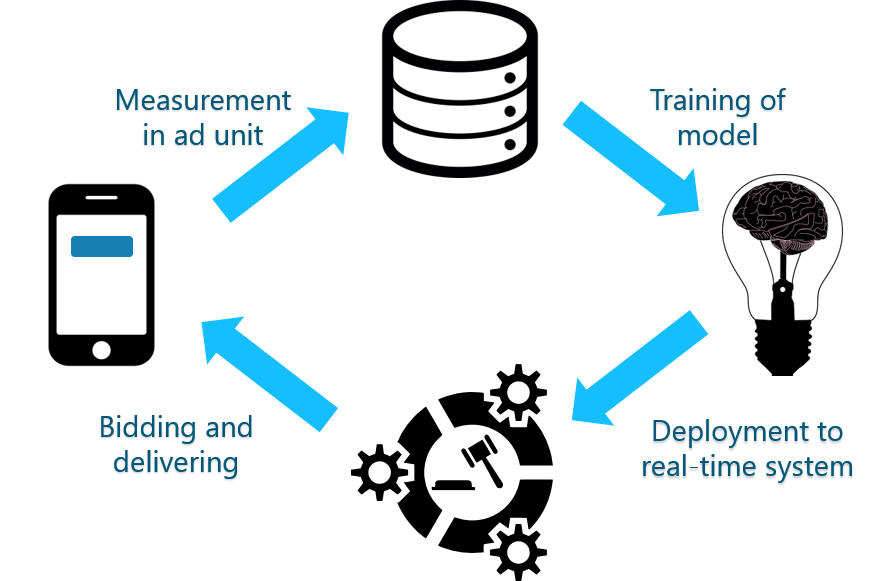

But we are buying impressions. In fact, we are taking part in digital auctions for each individual impressions and bid a specific price in each auction. Thus, we cannot buy viewable impressions but need to relate the value of a viewable impression to the price we are bidding. The naive approach would be to take the average viewability rate of all websites and apps and decrease the bidding price by that. It is possible, that this is working, but since you would decrease the buying price by an considerable fraction, the available inventory might just be too low or too bad in quality. Alternatively, you could select websites and apps with a high viewability rate and only deliver on them. This approach might be feasable, but it involves a very high degree of manual optimization and you’d still need to decrease the bidding price. Plus, it only makes use of one information (the publisher) while a lot of other information might be related to the viewability rate. Therefore, we use machine learning in order to weight the price of each individual offer by the probability of viewability.

Training

We train two independent machine learning models, one for measuring viewability and the other one for the viewability itself. As explained above, the measurement is a technical challenge. Therefore it is influenced by technical parameters like browser version or operating system. On the other hand, the viewability is influenced mostly by the publisher, the ad unit itself, and the position on the site. Since the relation between those features are very different for the different metrics, we separate them in two independent models.

Illustration of properties related to viewability.

Illustration of properties related to viewability.

Based on historic data, we have a ground truth dataset in the form:

impression ID measurable viewable features 1234 1 0 list of features 1235 1 1 list of features

The features consist of various properties of the context (e.g. app/site, position on the site), the content (e.g. size of the ad unit), and the user and device (e.g. operating system, browser version). For the measurement model we take all impressions and use the measurable column as target in a supervised classification model (namely a Neural Network). After a successful training, the output of this model can be interpreted as the probability of impressions to be measurable. The training of the viewability model only uses impressions, which are measurable, and uses the viewability column as target. Thus, this model provides the probability for viewability given the measurement was successful. As a consequence, the total probability for viewability is:

We perform a training of the model combination every couple of hours to be sure to make use of all recent campaign and publisher data.

Application

We can use the combination of the two models in our real-time bidding platform to get the probability for each impression we want to bid on. Then, we can scale the bidding price with this probability. So, if a viewable impression has the value of one cent to us and the probability of a view is 50%, we are bidding half a cent. If we buy two impressions with that probability for that price, we will get one viewable impression on average and pay one cent. Mission accomplished. There are two note-worthy aspects to this: First, we do not buy the viewable impressions for the cheapest possible price. This is approached with another mechanism. We are buying the viewable impression for a defined price and can allways be sure, to buy for that price or lower. This allows us to offer viewable impression for a defined price to our customers without the risk over over-paying. And second, this mechanism does not necessarily improve the rate of viewable impressions. We do not care if we buy many impressions with a low viewability rate or a few with a high. Since the potential customer only cares about viewable impressions, this is OK.

To sum up, the general data flow can be vizualized by the following graph.

General data flow.

General data flow.

Monitoring

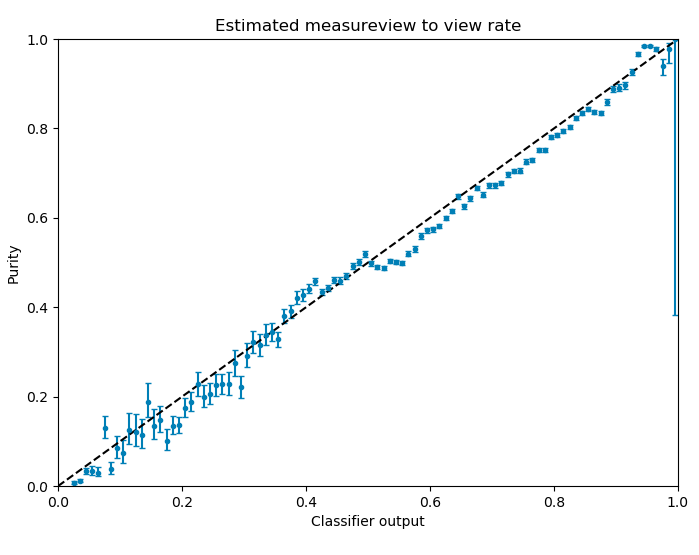

But this whole idea only works, if we have two classification models which give us an unbiased probability. Thus, if the output of the model is 0.5, half of the impressions should lead to a view. A lof of data-science libraries support this kind of output but many aspects of the data and the model can break this concept. Therefore, we monitor this capability by regularly producing and checking the following plot:

On the x-axis you can see the output of the machine-learning model. On the y-axis is the ratio of events (fraction of measures/views) in a bin of the output. If the output of the model is a probability, the data points should all lie on the diagonal y = x within a given uncertainty. This uncertainty originates from probabilistic nature of the underlying numbers.

Based on plots like this, we judge and monitor the performance of our delivery. As you can see, the relation is not perfect, but it is well within the requirements of the approach.

I hope, this gave some interesting insights into our system. There are many more aspects to this system: The specifics of the model itself, the pitfalls in the measurement, the integration into the real-time system,… But the article is already long enough. If you are interested in something specific, we would be thrilled hearing from you :)